by Rachel Signer

Champagne might seem like a “classic” wine, but the region has come a long way. No longer a wine designated for celebration, but rather valued in its own right as a terroir-driven accompaniment to fine food, Champagne has undergone something of a revolution in recent years — and it’s largely due to the rise of small growers, who began bottling their own wine instead of selling it to larger houses in recent decades.

Sommeliers have come to love grower Champagne because of the singularity of the wines, as well as the links between small production wine, and organic and sustainable viticulture. While Champagne houses are admired for reliably producing great wines year after year, there is more vintage variation in grower Champagnes, explains Sommelier and General Manager Allie Poindexter of Henrietta Red in Nashville, Tennessee. “If you care about where grapes come from, how they are farmed, and a sense of time and place from your wine, then you care about grower Champagne,” says Poindexter, who cites Pierre Moncuit’s “mineral driven, pure and elegant” wines as one of her favorite growers, along with R. Pouillon & Fils and Jacquesson. She offers a simple and helpful definition of grower Champagne: “The people who are producing the wine are also growing the grapes.” This means full control of the winemaking, from vineyard to glass.

Writer Peter Liem, who lives in Champagne and writes ChampagneGuide.net in addition to recently publishing a thorough guide to the region and its producers, emphasizes that grower Champagne isn’t necessarily “better” than the houses, despite its current visibility. “A misconception that persists is that grower Champagne is somehow intrinsically superior to house Champagne, which is far from true,” he says. “There are excellent growers and mediocre growers, and excellent houses and mediocre houses.” Liem concedes that there has been increasing divergence between the styles of growers and houses; “grower [C]hampagnes can be more inclined to stray from classical norms, and it’s possible for growers to take more risks making comparatively tiny quantities of wine.“

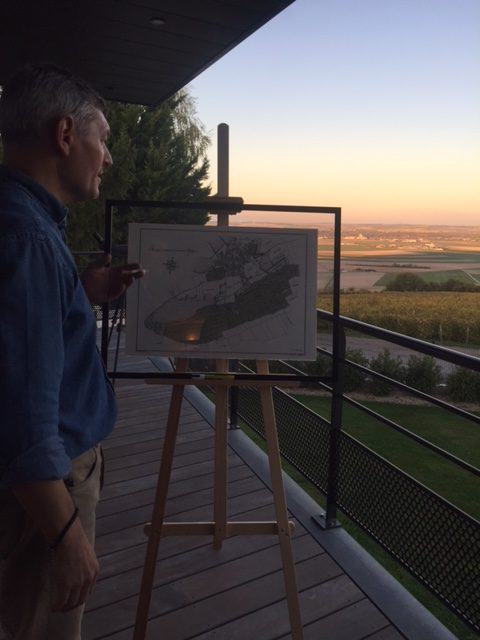

On a recent visit to prominent grower Anselme Selosse, whose wines are prized for their singularity, he professed the same sentiment: “We aren’t better than the grandes maisons,” he said as we tasted his robust, saline “Initial” wine, made from three consecutive vintages (2008,2009,-2010, in this case). It’s important to Selosse to have “humility and conscience” with respect to the broader community of Champagne producers, rather than assuming superiority, he explained.

Indeed, there are commonalities between Champagne houses and growers: Houses like Roederer and Veuve Clicquot make single-vineyard wines, and Roederer has notably made a low-dosage 2009 Brut Nature wine, in collaboration with designer Philippe Starck, who made the wine’s label. And the trend of low- or zero-dosage sparkling wines, often associated with grower Champagnes, also has roots amongst the houses: the Côtes des Bar house Drappier has long been making a Brut Nature, to name one example.

The grower movement is small in size, yet it’s influential in sommelier circles. “In terms of volume, the houses dominate the market, with over 70 percent of sales in volume globally and over 88 percent in the U.S.,” says Liem. According to the Comité Interprofessionnel du vin de Champagne (CIVC), the region’s marketing and quality control association, in 2016, grower Champagne accounted for just 4.9 percent of U.S. sales by volume, he adds.

But after 20 years of widespread exposure in the U.S. market, Liem has seen grower Champagne achieve “a sort of critical mass, ensconcing itself in the public wine-drinking consciousness.” It’s not hard to see, just stop by a wine-focused restaurant in any U.S. city, and you’ll find sommeliers entranced by the uniqueness of growers — a few personal favorites include Compagnie de Vins Surnaturels in New York City; Bar Vivant in Portland, Oregon; The Four Horsemen in Brooklyn, NY; San Francisco’s Zuni Café and Foreign Cinema.

Despite this affection, however, the line between growers and houses is blurrier than it may seem. In fact, some growers, or winemakers who are perceived as growers, also purchase grapes. In Champagne, any grower whose production includes at least 5 percent of purchased grapes automatically assumes the “NM” (négociant manipulant) status allotted to houses, rather than the RM (récoltant manipulant) status reserved for growers.

Fred Savart, whose family has been making Champagne for three generations in the Premier Cru Pinot Noir village of Écueil (they started bottling their own label in the 1960s, along with many other growers), began purchasing grapes about two years ago. “We love wine, and we want to vinify other sites,” is how Savart explains this move. He adds that “it’s a little like the Burgundian model,” meaning, he can work with unique, small vineyards and develop a deeper understanding of terroir through buying grapes from other small growers.

In the village of Montgueux, winemaker Emmanuel Lassaigne, who has always held NM status despite often being anecdotally grouped with growers, experiments with single-vineyard, single-vintage bottlings using purchased grapes from various sites around the region for a similar reason — it’s to “explore the terroir of Montgueux” and better understand it, he explains. Another former grower who began purchasing grapes in recent years is Raphaël Bérêche of Bérêche et Fils.

Liem offers another, very practical reason for this emerging trend: “Today the price of land is ridiculously expensive, if it’s even available for purchase, and we’ll be seeing many more RMs switching to NMs as it’s the only way to grow volume,” he says.

Regardless of whether the wine being poured is from a grower or house, there is a strong movement among passionate sommeliers to enjoy Champagne as a food pairing. “The carbonation in Champagne, along with its high acidity, makes it a delicious food wine,” says Henrietta Red’s Poindexter. “Many rosé Champagnes can stand up to heftier, meatier dishes, whereas a blanc de blanc may be a great pairing for salads, crudos, and creamy pasta dishes.” Growers, houses, whichever you prefer or are lucky enough to enjoy — it’s undeniable that Champagne has never been more exciting to explore than it is now, in terms of diversity of approaches and new discoveries of the region’s terroir.