story and photos by Rachel Signer

It’s a warm spring day in Australia’s Yarra Valley when Mac Forbes and I pull up to his most prized Pinot Noir vineyard, a place called Woori Yallock, which he makes into a silky-toned, softly tannic wine with the same name. We park alongside the eucalyptus-lined road and get out of the truck, but as I start to open the gate, Mac stops me and points to the basin of chlorinated water on the ground.

“If you don’t mind,” he says, and demonstrates, stepping his Rossi boots — the hallmark of every Aussie winemaker — into the water, smiling. “Just thirty seconds.” I’m next, of course. During the harvest season, Mac tells me, he requires his pickers to wear disposable coveralls in this own-rooted vineyard, meaning that Old World, European rootstock is still in the ground here. The risk of phylloxera is too great here to allow for carelessness.

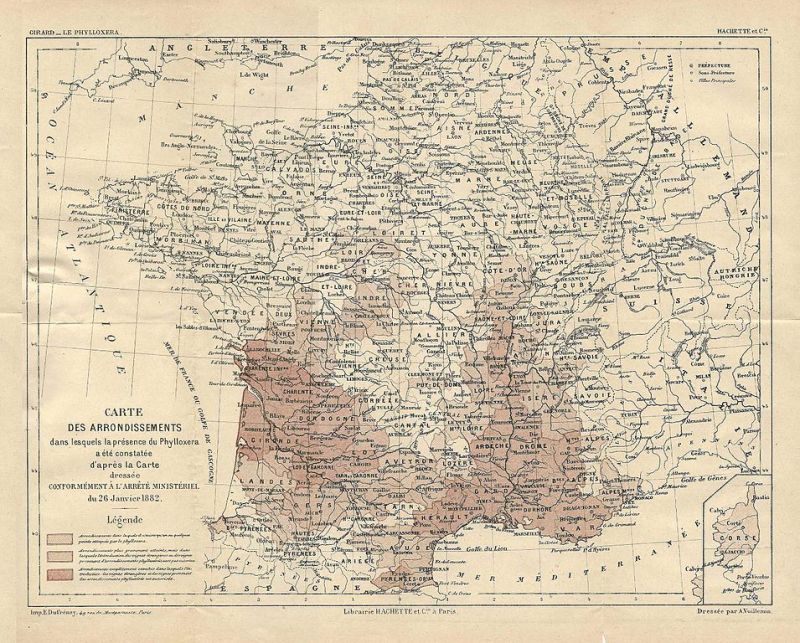

It may seem implausible that a pesky, stubborn, sap-drinking plant louse is one of the most important players in the global wine industry — and the reason why certain bottles in your cellar are more special than others — but it’s true. Phylloxera, an aphid-like bug that notoriously destroyed significant parts of France’s vineyards in the 1860s, has been responsible in so many ways for today’s winegrowing culture — and all it took was one infected grapevine, transported to Europe by someone who envied or studied American viticulture, to destroy the wine production of an an entire continent.

Phylloxera, in short, is like a plague sent down from Bacchus because his winegrowers behaved badly. The time when it invaded France is somewhat poetically known as the “Great French Wine Blight.” Even today, this vine-destroyer is directly responsible for how our wine is made today. Growers all over the world deal with the constant threat or presence of phylloxera, and some have a few tricks up their sleeve to keep it at bay. Meanwhile, certain regions of Europe, the U.S., and Australia have never seen phylloxera — meaning bottles from those places have unique value.

As recently as 2006, phylloxera crept into the Yarra Valley from another region in Australia. Mac Forbes and other growers in the area take all the precaution they can. If someone walks in a phylloxera-infested vineyard, the risk is too great, that they’ll bring the pests with them into a healthy one afterward. For Forbes, this risk means endangering the quality of his wine. “Vine age is important,” he says, in determining a wine’s complexity and uniqueness. I thought of the wines I’ve drunk that were made from older vines — they always showed more nuance and concentration than other wines. Forbes is also grafting American rootstock onto the Pinot in this precious vineyard, just as a precaution.

It’s a nerdy topic, for sure, but it’s quite fascinating to know how phylloxera works. I reached out to Oregon viticulturist Mimi Casteel for some help with this. Out of necessity, she researched phylloxera extensively to deal with its presence at her family’s vineyard in the Willamette Valley, Bethel Heights. “Phylloxera does not kill the [vine] plant,” she explains. “Rather, it opens the door to secondary, usually fungal or viral pathogens to infect the roots and move systemically through the plant.”

Phylloxera’s presence in the roots of vines meant that European rootstock had to be ripped up and replaced by American rootstock — which, it turned out, was more resistant to phylloxera. This, along with much experimentation in growing hybrid grapes (European Vitis vinifera bred with native American grapevines, known as Vitis labrusca), was done toward the end of the Nineteenth Century. And the French regrew their vines, and rebuilt their industry. But it hasn’t disappeared completely, as I saw during my visit to Mac Forbes. Meanwhile, certain regions around Australia, namely South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and Tasmania, are still entirely phylloxera-free. Rigorous care must be taken to prevent its spread to these own-rooted vineyards.

Phylloxera also reared its ugly head in California in the 1870s. There, the response was to graft clean European Vitis vinifera onto their rootstocks. The effects have carried through to this day. A type of rootstock called “AXR” was promoted in California as phylloxera-resistant for about 80 years, recalls David Bos, who managed the vineyards at iconic state winery Grgich. Interestingly, he says, many of the AXR vineyards began having phylloxera issues when they began using fertilizers and irrigation in the 1980s, fostering “a nutrition source that allows phylloxera to thrive.” One Grgich vineyard, a Chardonnay site in Carneros, which is on the AXR rootstock, has phylloxera still, he explains. They were on the verge of pulling out the vines, but they hesitated “because the fruit was still good,” says Bos. Instead, he began shifting to organic farming. The result was that the vineyard stabilized itself and now makes elegant wine. Again, the tactic managed to preserve older vines.

Some of the world’s most special wines come from islands, like Greece’s famously beautiful Santorini and Spain’s Canary Islands, which never experienced phylloxera because the pests can’t thrive in sandy soils. It’s hard to even know the age of some of the vines in these locations — they could be as much as hundreds of years old. Try Domaine Sigalas, Hatzidakas, Gaia or Argyros from Santorini to experience the depth and complexity of these wines, particularly those made with the island’s star grape, Assyrtiko. To add some visual drama, vines on Santorini are not only incredibly old, but also trained in the shape of a “basket,” to protect against wind.

In California, there are a few sites where phylloxera has never survived. The boutique label Sandlands, run by Tegan Passalacqua of Turley Vineyards, works with old vineyards, including some phylloxera-free ones which are “own-rooted” (meaning, on native rootstock) — such as, Carignan vines planted in 1915 in the Lodi region. Colares, in Portugal, is probably Europe’s most famous phylloxera-free region, thanks to its sandy soils (great wines, if you can find them — they are unicorns). In Oregon’s Willamette Valley, phylloxera is a presence that some viticulturalists have to deal with. Mimi Casteel says that, “caring for vines that are own-rooted and have or may have phylloxera . . . is all about fostering the immune system of the plant, which is almost entirely about the soil community.” To do this, she sprays compost/fungus teas made with cultivated soil-borne spores into the vineyard.

Can phylloxera ever be contained? Perhaps not. But there are places in the world that have been lucky enough to avoid it entirely — and you can drink those very special wines. On the bright side, it seems that the misfortunate presence of phylloxera is also pushing winegrowers to have a deeper understanding of plants and farming. Perhaps there are some blessings within this curse.